I first began to use digital cameras in the early 90’s while an active-duty combat photographer in the U.S. Army, and what I saw then, still continues to plague photographers today—a majority of photographers abandon money and megapixels when it comes to digital photography. They do this when they leave room in the camera viewfinder frame to crop their images later, or as I’ll explain, they burn one-hundred dollar bills subconsciously.

The back of my camera after I gave an image capture demonstration at my Orlando photography workshop.

While some will argue that this came about because the common traditional picture frames come in 5- by 7-inch, 8- by 10-inch and 11- by 14-inch, since the film days, others will argue because with the introduction of film there were 4- by 5-inch, 5- by 7-inch, and 8- by 10-inch film cameras. Still others will claim it’s a “framing industry” conspiracy to sell you mattes in order to make your full-frame image fit into a “standard” size frame—makes sense, buy a bigger picture frame to fit the matted smaller image.

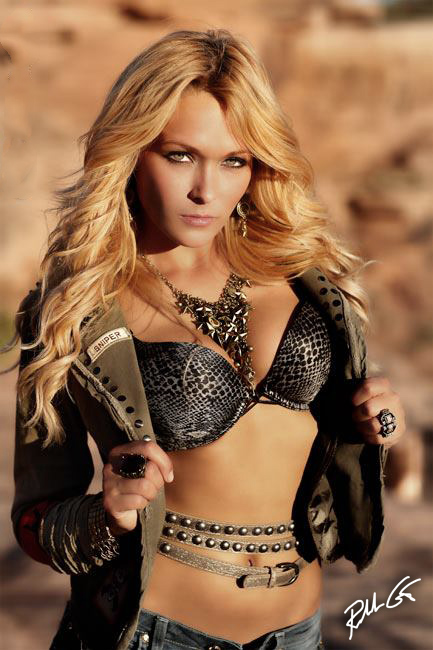

This is the full-frame version exactly the way it was framed in the camera’s viewfinder.

In the end, frame or no frame, if you’re the type of photographer that leaves room to crop your image later to produce a perfect 8- by 10-inch print, you just abandoned one-sixth of your original image captured. If your photo was captured with a 24-mega-pixel camera, that’s four megapixels down the drain, or in the case of a $4,000 camera, it’s the same as burning almost seven, one-hundred dollar bills.

Let’s do the math. A 35mm format camera, whether it’s film, DSLR, mirrorless or even a point-and-shoot camera produces an 8- by 12-inch, not 10-inch print, thus you lose 2-inches of the original photo captured in order to make your photo fit an 8- by 10-inch piece of photographic paper. Two goes into 12 a total of six times, or 2-inches, one 1/6th of 12-inches. Six goes into one, 0.16666666666667 times, but we’ll round off to .17 times to represent the fraction of 1/6, or one dived by six. Now take your .17 and multiply by $4,000, thus your solution, or loss, is $680, not to mention 24-megapixels divided by six is four abandoned megapixels. You can also divide $4,000 by six for a more accurate result rounded off to $667 as it’s a repeating six and no one likes three sixes in a row.

Again, this crop-your-full-frame-to-fit-picture-frame-mentality came in the early beginnings of photography and while I’m not sure who and why picked out those specific sizes, 35mm enlarged to reasonable sized prints for framing purposes, don’t fit.

My first thought is why do photographers crop outside the camera to fit the picture frame sizes? Part of that problem is the average photographer has never worked with a photo editor and had their images printed in a publication. My last thought is that most photographers tend to buy their cameras based on megapixel marketing hype, or on the Jones’s standard, “I have more megapixels than you.” Sad, but it’s true, many photographers think in 5- by 7-inch or 8- by 10-inch print mindsets—it’s time to think outside the box with digital photography. Cropping outside the full-frame of your camera is for farmers.

The other part of the why photographers abandon money and megapixels is we’re a society that has their brains programmed as we grow up in life. Most of us grew up with (in inches) 11×14’s, 8×10’s, 5×7’s and the 3 1/2×5’s, the latter made famous by the Noritsu one-hour mini-lab explosion of the 1980’s. Though the 3 1/2×5’s graduated to 4×6’s, our problems with mandatory societal-crops to fit frames, mattes, and photo albums didn’t originate with the most popular digital camera format today, the 35mm format.

Crop in the camera. Cropping outside the camera is for farmers.

If you purchased a 24-megapixel camera for $8,000 and are programmed in the crop-to-fit-the-frame-mindset, you will abandon 4-megapixels and over $1,330 subconsciously. The simple solution to avoid this dilemma is to fill your camera frame when you shoot, and make the picture frame fit the image, not the other way around. This practice to abandon money and megapixels isn’t the fault of photographers. Again, we’re programmed to accept certain things in life from birth.

The birth of the first 35mm format camera was invented by Leica in 1913, not Kodak. Kodak invented film and introduced the “135” for film, a 35mm wide film in a cartridge, but the actual film image area is 24mm wide as the other 11mm’s are used for the sprocket holes and spacing and the length was 36mm. It was based on metric units, not inches. It’s this format that led to the words, “full-frame” and sometimes “double-frame” in relationship to the “single-frame” 35mm movie format, which is another story in itself.

Now that you know the history of 35mm (135) film, let’s look at full-frame, because it’s this term you’ll hear photo editors tell photographers when it comes to their crops in 35mm cameras, especially if their photographs are for publication. A full-frame 35mm image makes (in inches) 4×6’s, 5×8’s, 8×12’s, and 10×15’s, thus to fit a full-frame photo into a “traditional” picture frame, a photographer would purchase a matte, with an opening cut to fit the full-frame image, thus the matte would then go into a larger frame—think costs to the photographer and client here. An 8×12, full-frame photo would then be matted to fit the larger and more expensive 11×14-inch frame.

When photo editors say, “Get it right in the camera,” they also mean crop it right, not just expose it properly.

On the other hand, photo editors harp at photographers not to crop in the camera, or not to leave space for placing an image in a frame for several reasons. One, primarily based on the old film days, is that 35mm is so small that leaving room to crop outside the camera makes the useful part of the photo even smaller. So, when this smaller portion of the photo is enlarged, it gets grainy, or in digital form, electronic noise and jagged pixel edges are more prominent, especially with older digital cameras. This holds even more relevance if the photo editor needs to crop your photo to fit the layout of a publication page. There is one exception, if you’re shooting a cover shot, the photo editor may ask to leave room at the top for the “flag,” or title of the publication.

But the other main reason photo editors harp on photographers to fill the frame when shooting is the fact that photo editors don’t place photos in a publication page based on frame and matte sizes, they publish and fit photos in a publication based on column inches and percentages—notice magazines or newspapers normally have more than one vertical column of text per page. Take a ruler and measure ten photographs within that publication, any ten. You’ll find various odd sizes and the chance of a photo being exactly to traditional frame sizes is rare. Not even the cover of a magazine is an 8×10, more like 8 1/2- by 11-inches in most cases, and the cover is one of the few cases where the original photograph is often cropped.

Now let’s take this one step further and pretend that a digital camera is purchased on the Jones’ theory of I’ve got more megapixels than you, where a photographer purchased a DSLR or mirrorless camera based on megapixels. Let’s pretend that digital camera is 24-megapixels and that photographer hasn’t read this article yet. So, that photographer will do what most amateur, non-published photographers do and leave room in all their photos to crop for that old 8- by 10-inch frame/print standard.

Now we know that a 35mm camera, film or digital, can produce an 8- by 12-inch print when printed full-frame. But the photographer wants an 8- by 10-inch print, which means that photographer will cut-off 2-inches from their full-frame, or 1/6th of the originally captured image. Now we take the camera’s 24-megapixels and divide it by the 1/6th loss and we have four. We then take that four and subtract it from the 24-megapixels and we now have a 20-megapixel camera—even though that photographer paid for 24.

Confusing? In simple terms, as we capture an image and leave room in the camera frame for the print and frame standards society has programmed us for, we lose 1/6th of our original photo, megapixels and money invested in that camera. Be different, don’t abandon your money and megapixels for the sake of traditional picture frames. And if your client or customer wants the programmed frame sizes, let them know that a larger print is better and the price is the same regardless–they’ll take the larger full-frame image. Take advantage of all the megapixels your camera offers, unless you can afford to burn hundred-dollar bills.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks